Mule Studio Essentials

Studio Overview

Studio is an integrated, two-way environment for developing, debugging, and deploying Mule ESB (Enterprise Service Bus) applications. To simplify application creation, Studio provides developers with a choice of tools — a visual, drag-and-drop editor and an XML code editor. The two editors work in tandem, thus making "round-trip" editing a reality.

The visual environment enables the developer to arrange building blocks on a composition canvas to create Mule Flows, which form the basis of Mule applications. A flow can include multiple inputs, branches, queues, calls to external resources, and multiple outputs, among other features. Simply drag-and-drop building blocks on the canvas to create a sequence of events that facilitate the processing of Mule messages. Each time a building block is inserted or deleted in relation to the other building blocks, Studio automatically updates the underlying XML file that contains all flow configuration information.

The visual environment also provides dialog boxes that typically accept plain English entries, rather than formatted XML, so developers don’t have to bother with XML syntax when configuring each building block.

However, developers already comfortable with XML may prefer to use Studio’s XML editor to set configuration details by writing XML statements directly into the XML configuration file. Studio makes XML coding easier by providing syntax guidance (suggestions for auto-completion) in real time and providing drop-down menus that list the available options for the XML attributes you are trying to code.

Developers can switch effortlessly between the two editing modes; Studio automatically records the building block relationships and set-up details, no matter which editor they use.

|

This documentation variously refers to the bundled system of software components that ships as Mule ESB (Community Edition), Mule Studio, Mule, or Studio. All these terms are fitting for this multi-faceted product. |

|---|

Mule Terminology

Mule ESB (Enterprise Service Bus) is a server environment that facilitates the integration of applications with each other as well as resources (such as databases, JMS queues, and file servers, etc.) throughout the enterprise and across the Web. Specifically, Mule provides the infrastructure that allows developers to assemble, configure, debug, and deploy applications that receive, process, and dispatch data in units known as Messages.

Messages are the functional data units, or packets, processed by Mule applications. For example, each customer order submitted to a Mule purchase fulfillment application qualifies as a message. Each message consists of a message header - which contains metadata, such as the sender of the message - and a data payload, which may contain XML, JSON, files, streams, maps, Java objects, or any other type of data.

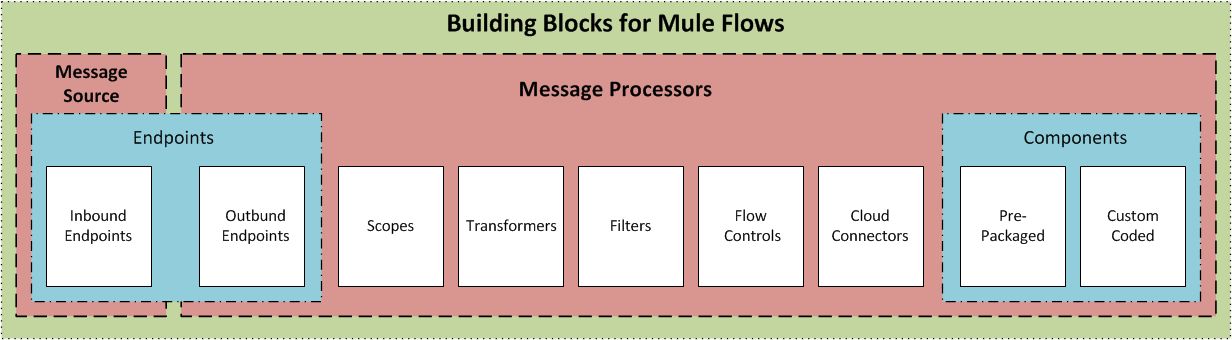

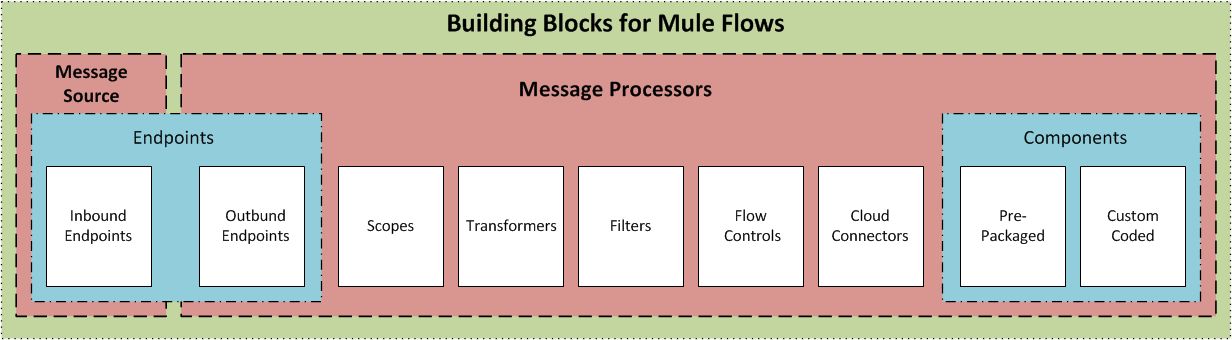

Building Blocks are pre-packaged units of business logic that come bundled with Mule. Two sub-categories of building blocks are worth noting:

-

Message Processors filter, alter, route, or validate messages within a Mule application.

-

Message Sources, also known as Inbound Endpoints, accept messages and trigger message processing within a Mule application. Technically, message sources, which receive messages, rather than process them, do not qualify as message processors.

Components fall into two sub-categories. The first group provides pre-packaged functionality such as logging and echoing. The members of the second group integrate custom-coded functionality into Mule applications. The custom code can be developed as a Java class, a Spring bean, or as a Ruby, JavaScript, Groovy, or Python script.

A Mule Flow resides at the heart of every Mule application, orchestrating the processing of messages by that application. Typically, a Message Source receives or retrieves a message, which triggers the main message processing flow. Each building block (i.e., message processor) in the flow evaluates or processes the message in some way. Simple applications consist of a single sequence (i.e., flow) of message processors, but complex applications can split into parallel branch flows as well.

|

This documentation sometimes appears to use the terms flow, application, and project almost interchangably. In fact, many simple applications implement only a single main flow, so in these cases, the terms are almost synonymous. However, complex applications can employ many child flows, both synchronous and asynchronous, which branch off the main flow. In the end, flows are the sequences of building blocks that orchestrate message processing, while applications are the computer code that executes on a server to implement some sort of functionality. Projects, on the other hand, include all the files, settings, data sets and other resources, such as icons, that are assembled to create applications or exhibit flows on the Message Flow canvas. |

|---|

Types of Bundled Building Blocks

| Building Block | Description | |

|---|---|---|

1 |

Endpoint |

A channel for sending and receiving data. An endpoint can be inbound or outbound. Inbound endpoints, which qualify as message sources, rather than message processors, listen for incoming messages on one or more channels such as HTTP or FTP, etc. Outbound endpoints, transfer data out of a flow; they can occupy the final position in a message processor sequence or, under certain circumstances, occupy a middle position. |

2 |

Scope |

A mechanism for grouping building blocks, messages or data payload parts so that they are treated as single units by other building blocks in the flow. |

3 |

Component |

Mule Components fall into two categories. The pre-packaged components initiate tasks ranging from logging to echoing. Components in the other subgroup allow developers to package business logic (custom-written as Java objects, Spring beans, or Python scripts, etc.). |

4 |

Transformer |

Changes the contents of a message (typically the data payload) before sending it to the next building block in the flow. For instance, a message received as XML might be converted into a map of columns and values so that it can be consumed by a database. |

5 |

Filter |

Determines where messages which meet certain criteria are routed within a flow. For example, a filter might discard all duplicate incoming messages that have already been processed. |

6 |

Flow Control |

Manages the transfer of data among building blocks. This can include branching, or the aggregation of data. |

7 |

Cloud Connector |

A special type of building block that connects a Mule application to a Cloud or Web-based API service such as Salesforce or Magento. |

Creating Mule Applications

After you have designed your project, creation of even the most complex application involves two main steps:

-

Selecting pre-packaged building blocks from the Studio Palette, then arranging them in a logical sequence on the Message Flow canvas.

-

Configuring each building block through Properties panels. Many of these panels feature drop down menus listing all valid options, so you don’t even have to type your selection. Help balloons pop up when you mouse over attribute fields.

Mule’s Studio interface allows you to create and deploy your Mule application without writing a single line of XML code. All of the information expressed through the sequencing of building blocks on the canvas and through the dialog panels gets captured automatically in your application’s XML configuration file.

You can edit the configuration file directly in its XML format, but you can also return to Studio’s visual canvas and plain-English dialog panels to fine-tune your settings.

About Main Flows

At minimum, all Mule applications include a main flow. Building blocks within the main flow may spawn multiple asynchronous flows, branch into parallel processing streams, and include synchronous subflows, but in any case, the main flow remains the backbone of the application.

All main flows begin with a Message Source (i.e., Inbound Endpoint). This key building block listens for incoming messages on one or more channels, such as HTTP or FTP. Each incoming message triggers a flow instance that passes the message down the sequence of building blocks in the flow.

The message source determines which of two Exchange Patterns (One-Way or Request-Response) will define the flow. The first type accepts messages, but does not reply to the sender of the message. By contrast, a Request-Response flow requires the Mule application to send a reply to the sender.

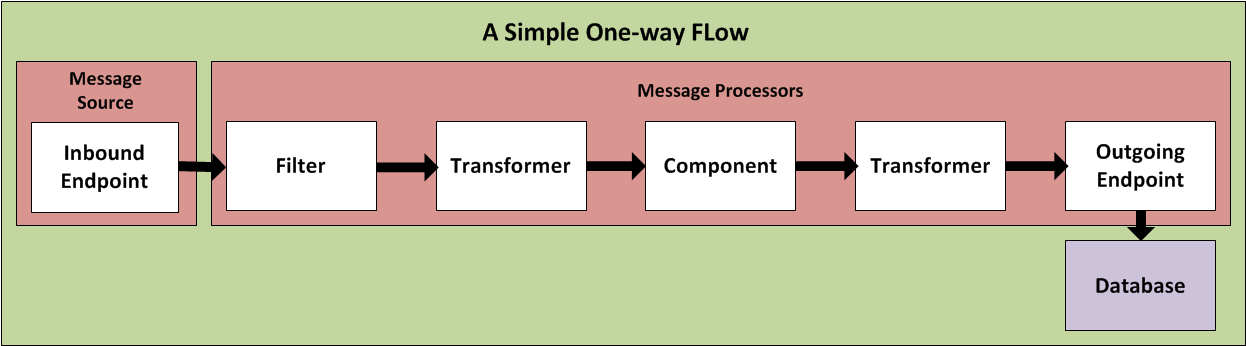

About One-Way Flows

The following Endpoints default to one-way exchange patterns:

Ajax  File  IMAP  JMS  Quartz  SSL  |

|---|

Typically, messages proceed straight through the building blocks of a one-way flow in sequential fashion, as illustrated by the following diagram:

For example, suppose our Mule application accepts holiday catalog requests which aren’t acknowledged or fulfilled until months later, when the printed materials are mailed. The Message Source, a JMS inbound endpoint, receives catalog requests from an external JMS queue. Next, an Expression filter checks the data payload, discarding messages with missing or invalid data. Messages determined to contain complete, valid data proceed to a JMSMessage-to-Object transformer, which converts the data payload into a Java object. Next, the custom-coded Component at the heart of the flow sorts the customer requests by catalog title and zip code, then adds a proprietary batch ID to the data payload, thus facilitating efficient mass mailing later in the year. Another transformer (Object-to-XML) translates the payload into XML so that it can be stored in a proprietary database. Finally, the outgoing JDBC endpoint uses the JDBC protocol to dispatch each processed message to the external database.

About Request-Response Flows

Certain endpoints - such as HTTP - default to a request-response exchange pattern. The full list of endpoints capable of request-response exchange patterns includes the following:

HTTP  RMI  TCP  |

|---|

Note that some of these endpoints also support one-way exchange patterns, if you override the default request-response setting.

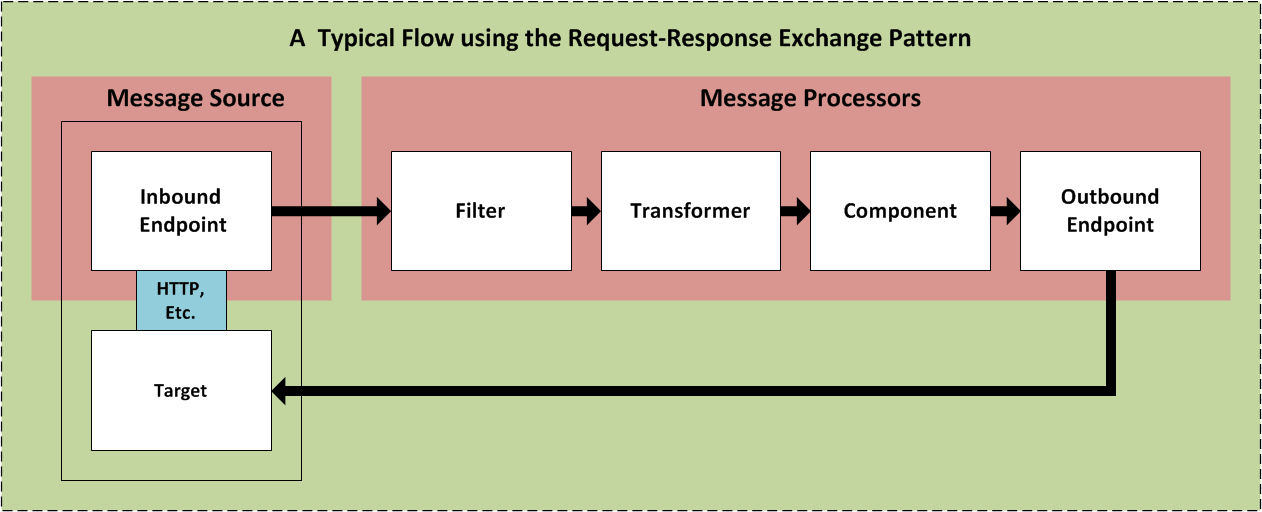

Whenever a message source requires that the sender of each message receive a reply (i.e., the message source specifies a request-response exchange pattern), the flow implements a request-response "loop", as the following schematic depicts:

For example, suppose we develop a new Mule application that receives, processes, and fulfills holiday catalog requests using the request-response pattern. The message source - an HTTP inbound endpoint using the FORM method and its default request-response setting - receives messages containing customer information, including the name of the specific catalog they want. An Expressions filter checks these incoming messages, discarding the ones with incomplete or invalid data. An Object-to-XML transformer converts the data payload from Java objects into XML. The custom-coded Component at the center of this application determines which catalog the customer wants, then retrieves that publication in PDF format. Finally, the SMTP endpoint, which serves as the flow’s outbound endpoint, dispatches the catalog to the email address provided by the customer who requested the catalog.

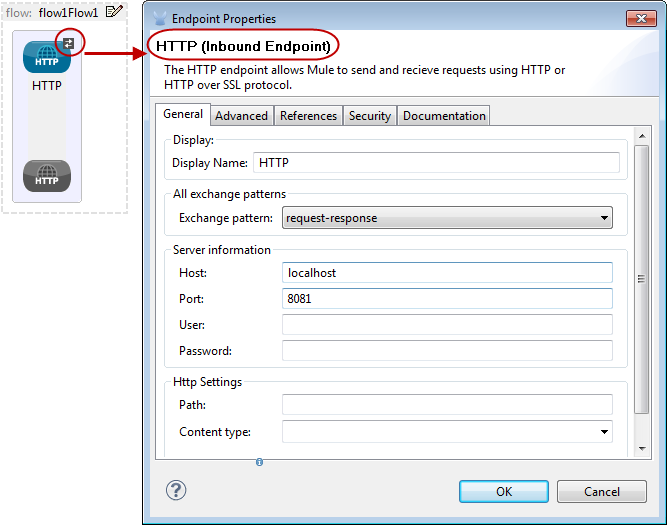

Visual representations of a request-response message source

When an inbound endpoint on the Message Flow canvas is set to the request-response exchange pattern, a special "double icon" appears, as the following image indicates:

A bi-directional arrow appears in the upper left corner of the double icon to indicate a request-response exchange pattern.

Where to Go From Here

For Tips and Tricks on using Studio’s various interface features, see:

If you have questions about Mule or the Studio interface, please take a look at our FAQ page.

Keep on kicking!